The reclining woman’s light pink dress is disappearing before my eyes – the thick material of the ankle-length, long-sleeved dress becomes ever more pellucid until it is only an outline framing the woman’s naked figure.

In this video installation, the first work to greet you as you enter the Bare, Naked Nude exhibition at the Pera Museum, Özlem Şimşek offers a contemporary take on Halil Paşa’s 1894 painting Uzanan Kadın (unfortunately this painting could not displayed in the exhibition). Whereas the composition of Halil Paşa’s painting merely suggests a version of the ‘reclining nude’ pose – his subject is fully clothed after all – Şimşek’s video goes one step further by making the woman’s dress dissolve until she is, in fact, nude.

The story of the nude in Turkish art – how we went from Halil Paşa’s painting to Şimşek’s video installation – is the focus of this small but dynamic exhibition. By charting the evolution of nude painting from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, during the transition from empire to republic, the exhibition definitively demonstrates how nudes became one of the foremost genres in Turkish art, joining the ranks of portraiture, landscape and still life.

The representation of the naked human body is just that – a genre, as opposed to a subject. From its origins in ancient Greece, the nude became an important aspect of the Western European aesthetic and a primary educational tool through which artists learned anatomy and ratio. Live models were an indispensible resource: capturing their unlimited repertoire of poses and visual expressions allowed artists to develop the skills necessary for multi-figure compositions.

The first section of the exhibition explores this idea of the nude as an educational tool. Sketches of nude models by Turkish artists who studied at Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi – the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, established in 1882/83 – cover the wall and a faux eave.

![]()

Photograph courtesy of the Pera Museum Blog

The nook is reminiscent of a garret, and in this cosy, intimate space I felt as though I was wandering around a studio rather than a museum. The sketches range in date from early- to mid-20th century.

![]()

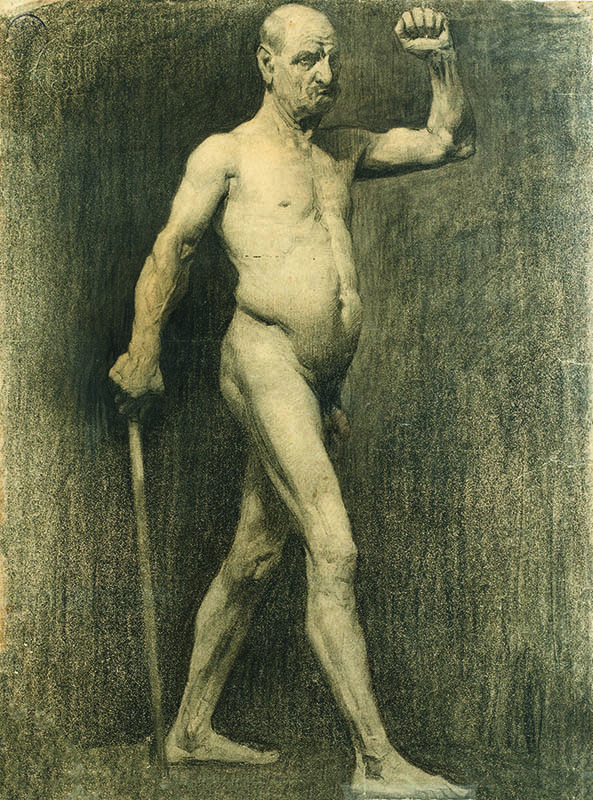

Mehmet Ruhi Bey, ‘Nü – Cormon Atolyesi’ (‘Nude – Cormon’s Studio’), 1912, pencil on paper, 62.5 x 47.5 cm, Esin Arel Tunalıgil Collection

There is a large number of male nudes. Mehmet Ruhi Bey’s sketch of a scowling man who looks ready to start a fight is a study in anatomy – no muscle or vein is overlooked. It is in the rendering of the model’s steadfast expression and wrinkled face, however, that Mehmet Ruhi Bey truly demonstrates his skill.

![]()

Nuri İyem, ‘Nü’ (‘Nude’), 1950, pencil on paper, 31.5 x 22 cm, Evin-Ümit İyem Collection

Fast-forwarding 40 years, Nuri İyem’s Nü (Nude) sketch is a cubist study of the female form. İyem plays with symmetry in a way that creates stark contrasts, while at the same time incorporating soft, feminine curves.

The cultural climate, specifically the public perception of nudity and the use of live models, differed greatly between when Mehmet Ruhi Bey made his sketch in 1912 (firmly in the midst of the Second Constitutional era) and when İyem’s sketch was completed in 1950 (more than 20 years after the founding of the Republic). While it was only marginally acceptable to use male live models in 1912, female live models were commonplace by 1950.

The story of Ottoman art’s engagement with this controversial genre, however, stretches even further back, to the mid-19th century. Although the first generation of artists sent to Paris in the 1860s – Osman Hamdi Bey, Süleyman Seyyid Bey and Halil Paşa, among others – made studies of live models there, it was understood that this subject matter would not be tolerated in Ottoman territory. Cultural motivations, described variously as tradition, custom, practice and virtue, lay claim to the public portrayal of bodies.

![]()

Nude postcards similar to the one above further blurred the lines between art and obscenity. This poscard is from a later date – 1907 – but they first entered the Ottoman Empire in the 1890s (Seyhun Binzet Collection)

The transformation of Ottoman visual culture in the 19th century, which ran parallel to the modernising Tanzimat reforms, had enough hurdles to overcome in the popularisation of Western-style painting and other art forms with which the public was unfamiliar. Thus the issue of the nude, which required stripping the naked human body of its sexuality, was always on the agenda for the next generation.

Starting in 1902, students at the Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi began to use live models – men only, and often wrestlers – in their drawing and painting classes. These male models began to pose nude in 1906. Yet it was not enough for this generation of art students, who had learned of the presence of nude female models in European art schools and unsuccessfully lobbied the authorities for the chance to draw from live female models in the academy. The use of men as opposed to women may be understood as an obligation, not a preference. Some of the rare examples of these works are on display in the exhibition.

![]()

Hikmet Onat, ‘Erkek Model’ (‘Male Model’), undated, oil on canvas, 71 x 43 cm, Merey Collection

Hikmet Onat’s undated oil painting of a male model wearing a loincloth is a compelling attempt at capturing the internal structure of the human body using broad, dark shadows.

It was only in the 1920s that paintings of naked women were publicly displayed. Namık İsmail, İbrahim Çallı and Melek Celal Sofu, three artists who studied in both Istanbul and Paris, showed their sumptuous nudes at the Galatasaray Exhibitions, which were sponsored by the Ottoman Painters Association and became a fixture of the Turkish art scene during the early Republican era.

![]()

Namık İsmail, ‘Çıplak’ (‘Nude’), undated, oil on plywood, 81 x 65.7 cm, Private Collection

My favourite of these paintings on display at Pera is Namık İsmail’s Çıplak (Nude). While most of the artworks in this section of early nudes depict the woman from behind, often reclining, this painting features a woman facing forward, kneeling on the ground and leaning on her left arm. Despite this forward-facing position, her gaze is downward – she could almost be asleep – suggesting shyness. The tension created by the focus on her torso and breasts, which are rendered in bold, dramatic brushstrokes and bathed in light, and her introverted gaze makes the painting feel intimate and sensual.

![]()

Mihri Müşfik, ‘Aynalı Gözde’ (‘The Sultan’s Favourite with Mirror’), undated, pastel on cardboard, 85 x 68 cm, Suna–İnan Kıraç Collection

After contextualising the rise of nude painting in the early 20th century, the exhibition divides into sections showing different types of nudes. Many of these are undated, such as Mihri Müşfik’s work Aynalı Gözde, the most riveting piece in the section on nudes with mirrors.

![]()

Neşet Günal, ‘Dörtlü Güzellik’ (‘Four Beauties’), oil on canvas, 136 x 126 cm, Gregory M. Kiez & Mehmet Kutman Foundation Collection

Those that are dated are mostly spread between the 1930s and 1950s, including my favourite of the allegorical nudes, Neşet Günal’s Dörtlü Güzellik. This large painting from 1951, which features four women in various poses, is reminiscent of Gaugin, but with female bodies that are outsized and almost cartoonish in shape.

It’s tempting to mark the creation of the Turkish Republic as a milestone – a divider between the old and the new, the dated and the modern. However, the desire of artists to paint nudes, and their subsequent chafing at and agitating against cultural restrictions, was a social dynamic that existed before the Republic was founded and continued during its early years.

Yet one cannot deny the strides that were taken in the first decade of the Republic. Under the directorship of Namık İsmail, Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi was made co-educational in 1927 and training with live models – both male and female – became a part of the curriculum. Full integration, however, was an ongoing process as opposed to an immediate change, as evidenced by photographs from the period in the exhibition book. Public perception of the nude was also by no means a settled issue, and debates over whether nudity in painting was obscene continued well after the Republic was formed.

![]()

Zeki Kocameni, ‘Çıplak’ (‘Nude’), 1941, oil on canvas, 93 x 72 cm, Sema-Barbaros Çağa Collection

The remainder of the exhibition demonstrates how artists in the Republican era developed their own artistic identity and style through the nude. In a section dedicated to the repertoire of nude poses, Zeki Kocameni’s painting Çıplak is a colourful take on the standing nude and has the inklings of modernist forms.

![]()

Cemal Tollu, ‘Pencere Önünde Model’ (‘Model in Front of the Window’), Paris, 1939, oil on canvas, 64.5 x 50 cm, Lucien Arkas Collection

Cemal Tollu’s seated nude in Pencere Önünde Model (Paris, 1939) also shows the artist’s gravitation toward modernist movements. This painting drew me in and held my attention for quite a while, mainly because the subject seems forlorn. It’s as if she is a part of the city – at least in terms of shared colour – while still being an outsider, with her curves juxtaposed against the straight lines of the urban roofs and chimneys.

![]()

Sabri Berkel’s ‘Odalık’ (‘Odalisque’), 1951, oil on cardboard, 60 x 47 cm, Fatma Saka Collection

It is stirring to see the stylistic diversity that began in the 1930s, especially once one has gained a better understanding of the battle to introduce the nude to Turkish art. Through this genre, often utilised in a painter’s earlier period due to its place in art education, it is possible to observe the ways in which Turkish painting expanded into new forms of expression and perception. Sabri Berkel’s Odalık, for instance, is an explosion of colourist ecstasy which displays a desexualised female body.

![]()

Bedri Rahmi Eyüpoğlu, ‘Çıplak’ (‘Nude’), c 1930, oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm, Lüset-Mustafa Taviloğlu Collection

The exhibition ends by focusing on four artists in their search for style. It was particularly intriguing to see how some of Turkey’s most prominent modernist painters forged their understanding of form through the nude. Eren Eyüpoğlu and Bedri Rahmi Eyüpoğlu produced a number of nudes that were in a conversation of sorts, while the series of nude paintings by Bedri Rahmi Eyüpoğlu show his stylistic development, from figurative works, like Çıplak, above, to more abstract pieces.

The Pera Museum has expertly told a fascinating story of modernisation in Turkey through the medium of the nude. It is remarkable that the museum and the show’s curator, Ahu Antmen, managed to present such a cohesive exhibition, considering that many state museums holding significant examples could not lend works due to the process of inventory-checking. Regardless, they were able to reveal the history of the nude in Turkish painting and the challenges it posed to both form and culture – something lovers of history and art history alike will delight in.

Main picture: Özlem Şimşek, ‘Uzanan Kadın (Halil Paşa'dan Sonra)’ (‘Reclining Woman (After Halil Paşa)’), 2012, video, 01.27 loop, courtesy of the artist.

You can visit ‘Bare, Naked, Nude’ at the Pera Museum until Sunday, February 7.

![]()

The book of the exhibition is available from Cornucopia’s bookshop at £16.75.

The exhibition is featured in the Connoisseur pages of Cornucopia 53.

Omonoia Square, Athens, 1900

Omonoia Square, Athens, 1900 Weevil larvae of the ‘Rhynchophorus ferrugineus’

Weevil larvae of the ‘Rhynchophorus ferrugineus’ Omonoia Square, 1927, construction of the ventilation shafts for the train station below

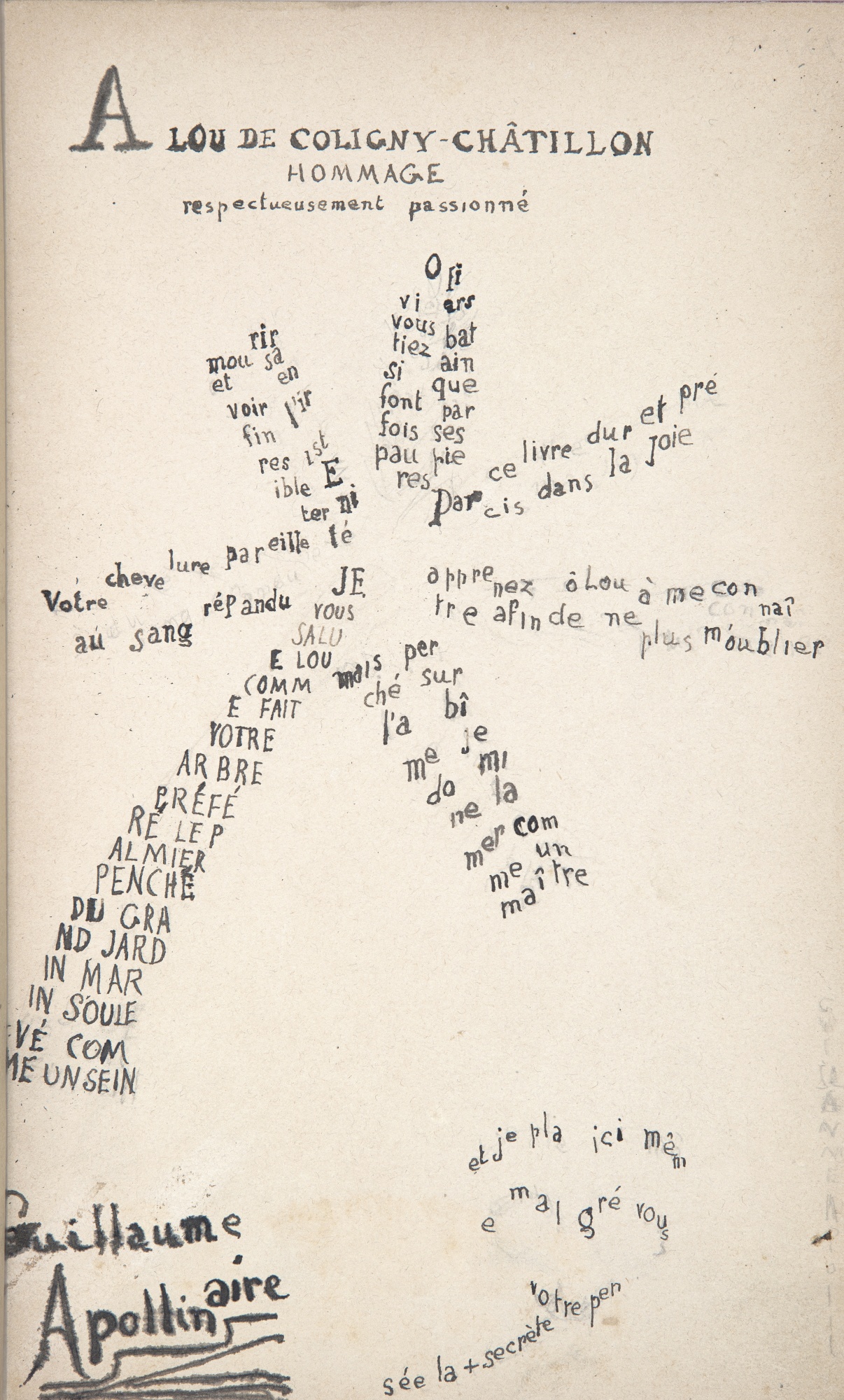

Omonoia Square, 1927, construction of the ventilation shafts for the train station below Guillaume Apollinaire, Hommage à Lou de Coligny-Châtillon

Guillaume Apollinaire, Hommage à Lou de Coligny-Châtillon

Peter Cook in Bedazzled (1967)

Peter Cook in Bedazzled (1967) Palm Tree Telecommunications tower, photographed by Dillon Marsh

Palm Tree Telecommunications tower, photographed by Dillon Marsh Komt Hier Aan Deze Gelen Vlaktes, Probe, Arhem, 2015

Komt Hier Aan Deze Gelen Vlaktes, Probe, Arhem, 2015 Study for Imagine A Palm Tree, by Navine G. Khan-Dossos, 2015

Study for Imagine A Palm Tree, by Navine G. Khan-Dossos, 2015 Palm Tree, Keramikos district, Athens

Palm Tree, Keramikos district, Athens

_dining_room_by_Monica_Fritz_for_Cornucopia_53.png)