Above: Hoca Ali Riza’s ‘Conversing by Moonlight on the Bosphorus’ (courtesy of the Ferda–İbrahim İpeker Collection)

Notes on the first in the Orient Institut Istanbul's series of talks, Reclaiming Istanbul: Public Spaces in Past and Present: The Kahvehane, by Dr Cengiz Kırlı, a lecturer at Boğazici Univeristy and author of Sultan ve Kamuoyu (The Sultan and Public Opinion)

‘Istanbul, One Great Coffee House’ was the subtitle of Cengiz Kırlı’s talk launching the Orient Insitut's excellent winter lecture series on October 17. From the moment coffee reached Istanbul in the 16th century, spreading from there far and wide across Europe, the kahvehane, or coffee house, became Ottoman Turkey's traditional social venue. Little is known about the city's coffee houses before the 18th century, but we know that Muslim opposition to the 'evil’ substance on the part of Süleyman the Magnificent’s şeyhülislam Ebusuud Efendi led to a ban on coffee houses. Yet survive they did, becoming hotbeds of political debate; it is easy to imagine rebellious conversation fuelled by coffee and nargile. By 1790, almost half Istanbul's coffee houses were being run by Janissaries, members of the Sultan's standing army, who increasingly used their position in the state to further their own interests.

In 1835, nine years after abolishing the Janissary corps in the famous Auspicious Event, Mahmud II (r. 1808–39) established a network of multi-lingual informers to report back on political chatter in coffee houses, and it is this period that has been the main focus of Kırlı’s research. When Abdülhamid II (r. 1876–1909) later become notorious for using similar tactics, he was, in Dr Kırlı's view, out to capture and condemn. Mahmud II, by contrast, simply wanted to keep an eye on what was being talked about. Kırlı argues that Mahmud II’s informers in fact represented the first systematic attempt at a survey of Ottoman public opinion.

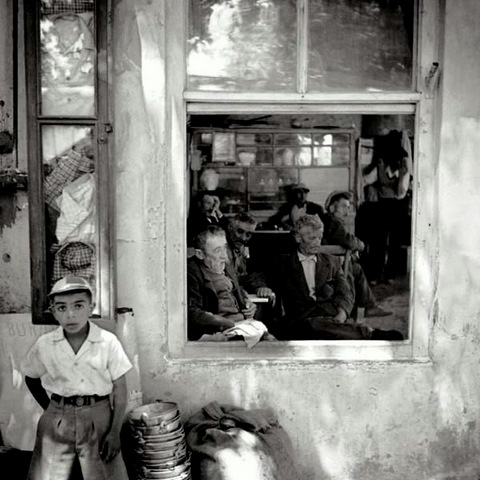

'N’olucak bu memleketin hali?’. A Coffee House in Kartal, 1956. Ara Güler

Coffee houses functioned much as specialist journals do today. One went to a coffee house in the port of Galata to hear news from sailors and merchants; in a coffee house in Beyoğlu it was all ambassadors' and diplomatic gossip. Everyone in the society knew exactly where to go to gather a certain kind of information. One can hardly imagine coffee houses fulfilling the same role now. But it is still tempting to wonder 'what if' a version of the old Ottoman coffee house had been kept alive. Today's kahvehanes tend to be full of men idly playing cards, or, in Starbucks and the like, young Istanbullus playing with their mobile phones. Yet every now and then one still hears the question 'N'olucak bu memleketin hali?’ (what's to become of this country?), and everyone still has something to say.

Sultan ve Kamuoyu: Osmanlı Modernleşme Sürecinde Havadis Jurnalleri (1840–44), by Cengiz Kırlı, is published by İşbank Yayınları, 2009.

For English readers, Cengiz Kırlı expands on the role of coffee houses in his chapter 'Surveillance and Constituting the Public in the Ottoman Empire', published in Publics, Politics and Participation: Locating the Public Sphere in the Middle East and North Africa (edited by Seteney Shami, Social Science Research Council, New York, 2009)

The Orient Institut lecture series will continue until the end of February 2013 with topics ranging from street lighting to banchelor pads. See Reclaiming Istanbul for details.