A fascinating exhibition is on display at the Chamber of the Scrutinio in Doge’s Palace in Venice which traces the history of the diplomatic relations between the Republic of Venice and the Safavid Persia under the rule of Shah Abbas the Great (1587–1629). The exhibition specifically highlights the gifts exchanged between the two powers from 1600 until the end of the Shah’s reign.

The exhibition was inspired by Gabriele Caliari’s majestic painting depicting Doge Marino Grimani receiving the Persian ambassadors (above), which is on display in the Four Doors Room. The painting illustrates the friendly and lucrative relationship between the two powers, united by their common objective of fighting the expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

Curated by Elisa Gagliardi Mangilli and Camillo Tonini, the exhibition displays 30 pieces, including the gifts sent by the Shah to the Venetian Republic, as well as letters of presentation, documents, engravings, maps, coins and other objects. The above image shows a sumptuous ceramic cup from Persia from the 17th century (fritware, height 18 cm, diameter 42 cm, on loan from from the Correr Museum Library).

An important example showing the lavishness of the gifts presented by the Shah is the above silk carpet. Measuring at 258 x 181 cm, it is weaved in gold brocade and features detailed floral motifs (on loan from San Marco Museum).

Another example is the above piece, made from velvet and silk brocade and weaved with gold. Measuring at 136 x 136 cm, it depicts the Virgin and Child and is almost certainly the work of specialised Armenian craftsmen working in New Julfa in Isfahan (on loan from the Palazzo Mocenigo). Both of these textiles were presented to Doge Grimani by the Persian envoy on March 5, 1603, in the Sala del Collegio which is right next to the Scrutinio Chamber.

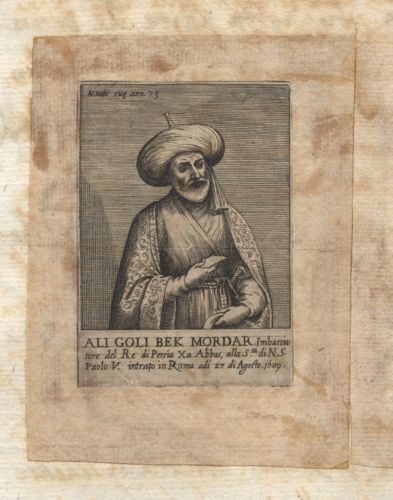

The exhibition also features several engravings which illustrate the protagonists of the time, portrayed in great detail by European artists. The depiction of these figures gives us a glimpse into the customs of the Safavid court and allows us to appreciate details such as the quality of the fabrics used for the clothing and the jewellery fashionable at the time. The above image shows an engraving of Ali Goli Bek Mordar in the book Three models of Venetia by Gioan Carlo Sivos (1595–1615), on loan from the Correr Museum Library collection.

There is also a section dedicated to the cartography of Persia, displaying maps and portolans used by travellers. The quality of these maps reveals the well-developed technical skills of the cartographers at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries. Of particular note is Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum orbis terrarium, the first ‘modern’ atlas to come in a pocket format. Published by Philip Gale in 1593, it measures at just 7.5 x 10.6 cm and is on loan from the Correr Museum Library. The above image shows a page from the atlas, illustrating Persia.

Also on display are 17th-century documents, including outstanding original firmans signed by the Shah, now kept in the Venice State Archive. There are also examples of detailed requests from the Persians for certain Venetian objects.

For both political and economic reasons, Venice played an active role in diffusing the West’s image of Persia that was characterised by an aura of nobility and prestige. Travellers of that period included Pietro della Valle, who said that the Persian army was made up of knights and gentlemen rather than dangerous, merciless warriors. The above image shows a page from Pietro della Valle’s Travels of Pietro della Valle, from his letters to Paolo Baglioni, 1664, printed publication, on loan from the Correr Museum Library.

Another aspect explored in the exhibition is the Shah’s countless victories in battle, which earned him the title of ‘the Great’. His refined taste extended to his weaponry. Of particular interest is the above shield – part of the armour which protects the lower part of the arm. Unfortunately, jewels and turquoise stones fell off the shield and the only testimony left to these decorations is a watercolour painting by the Italian painter Giovanni Grevembroch. The above shows the shield as it looks today. It dates back to the 16th century and is made from Indian cane, silk, etched metal and gold (height 20 cm, diameter 62 cm, on loan from the Palazzo Ducale).

The exhibition is on display until April 27, 2014.

Main image shows Gabriele Caliari’ s ‘The Doge Marino Grimani receiving gifts from the Persian ambassadors in 1603’, oil on canvas, 367 x 527 cm, displayed in the Four Doors Room.